Seal ultrasounds, fish MRIs and exotic animal endoscopies

UGA’s zoological medicine program provides practical experience for residents

Diego is a very well-behaved patient.

Waddles into the “office” on his own. Sits patiently as Dr. Jessica Comolli prepares the ultrasound machine.

When it’s time, he rolls into position, staying super still as Comolli slowly maneuvers the machine across his side and belly. Once the procedure ends, he hops right up and gets ready to head out.

He’s basically a perfect patient … except for the fishy smell.

Diego is a California sea lion. And he’s pumped for his ration of fish, a reward for being on his best behavior.

Comolli isn’t looking for anything specific this time. But practice runs in the behind-the-scenes holding area like this get the marine animals desensitized to the process. That way, if a medical crisis comes up in the future, it will be easier to get them the care they need.

“It lets them associate diagnostics with a positive experience,” said Comolli, the first graduate of the University of Georgia’s four-year zoological medicine residency program. Residents also earn a master’s degree in comparative biomedical sciences during the first two years of the program. “They’re getting their fish, and we’re getting our images of their gastrointestinal tract, liver, kidneys, or really any internal organs.” When she’s done, the sea lion hops back up at a cue from his trainer and bounces off to his enclosure.

Then it’s on to the next animal.

A veterinarian’s work is never done—particularly at the Georgia Aquarium, the largest aquarium in the world, housing thousands of aquatic animals.

Filling the zoological medicine veterinarian gap

Comolli always wanted to be a veterinarian.

“You can see in my first writings in kindergarten about what I wanted to be when I grew up that I was trying to spell veterinarian,” she said. “And I knew I wanted to work with everything—not just cats and dogs—from the very beginning.”

She took a bit of a “longer route” to vet school, becoming a licensed vet technician, the veterinary equivalence to a registered nurse, before earning her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree in 2016.

For her residency, there wasn’t much of a question where she wanted to go: UGA’s zoological medicine program.

There are fewer than 20 such programs in the U.S. that are certified by the American College of Zoological Medicine. Many of them focus on specific groups within the field, such as exotic pets or aquatic animals, and not all programs produce a specialist each year.

And the lack of qualified exotics experts in the veterinary world is a problem—a problem the University of Georgia wants to help solve.

“You would not be taken seriously if you said, ‘I’m going to be a dermatologist’ unless you did a residency in dermatology and were properly trained,” said Dr. Stephen Divers, director of UGA’s zoological residency program and a professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine. “And yet we still have a significant number of zoos and aquariums, which are specialty practices, that currently don’t have recognized specialists working for them. There are less than a dozen specialists being produced every year. That’s one reason why I think our program is critically important.”

Fish advanced imaging

The fish was huge.

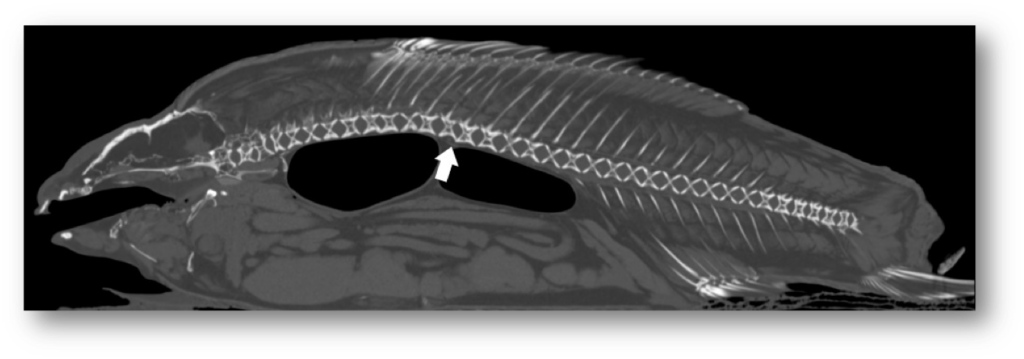

That wasn’t the issue, though. The real problem was that the 29-pound koi had a spinal injury.

But in order to know how to help the aquatic animal, the veterinarians had to clearly see what they were dealing with.

“Imagine trying to do an MRI with water,” Comolli said. “We had to come up with a way to not destroy the machine. By doing that, we could actually look inside the fish without having to do anything invasive.”

Comolli was in her first year of the program, and this fish’s situation was a pickle.

Consulting with a variety of experts at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, she and the rest of the team developed a technique that allowed veterinary staff to perform MRIs and other cross-sectional imaging on the fish, something that wasn’t previously commonly done.

A mutually beneficial partnership with Zoo Atlanta and Georgia Aquarium

Fish imaging was just one of many unusual animal procedures Comolli participated in during her first two years as a zoological medicine resident.

Residents spend those years practicing at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital under the supervision of Drs. Stephen Divers and Jörg Mayer. There, they treat a variety of reptiles, birds, mammals and even fish, and collaborate with experts in anesthesia, surgery, ophthalmology, cardiology and more.

In addition to seeing patients at the hospital, the residents head into the field to care for animals at Bear Hollow Zoo and Sandy Creek Nature Reserve. During their time at the teaching hospital, they also participate in research and earn their master’s degree.

But what really sets UGA’s zoological medicine residency apart comes during residents’ third and fourth years.

The residents spend their final two years in Atlanta, first at Zoo Atlanta and then the Georgia Aquarium. Most zoological medicine programs focus on one of the main areas of zoological medicine: exotic pets, zoo facilities or aquariums.

UGA gives residents a taste of each, something few programs offer worldwide.

“This residency allows us to choose after the fact,” Comolli said. “We get to experience those different disciplines and then decide what our calling is.”

The partnership among Zoo Atlanta, the Georgia Aquarium and UGA is mutually beneficial.

“Zoo Atlanta is fortunate to be able to participate in the four-year residency training program in zoological animal medicine in partnership with the University of Georgia and Georgia Aquarium,” said Dr. Sam Rivera, senior director of animal health at the zoo. Rivera is also adjunct faculty at the College of Veterinary Medicine. “This high-caliber program provides exceptional, well-rounded training to veterinarians seeking a career in this field and is second to none.”

And the residents bring information about the latest new drugs, techniques and procedures to the facilities.

“Georgia Aquarium’s clinical veterinary residency program, in partnership with the University of Georgia and Zoo Atlanta, provides a unique hands-on learning experience with a wide range of taxa that enhances career opportunities for these talented young veterinarians,” said Dr. Tonya Clauss, vice president of animal and environmental health at Georgia Aquarium. “As leaders in aquatic animal care, we are proud to be a part of educating the next generation of animal health specialists.”

It also provides the facilities with a bank of zoological medicine specialists to call upon when they’re short-staffed or hiring.

Since completing the multidisciplinary program in 2021, Comolli has done relief work in a specialty referral practice and an aquarium, and will be starting at a zoo soon. “That’s not something every veterinarian that finishes one of these residencies can say they are comfortable doing,” she said.

Life after veterinary residency

When the harbor seals come galumphing down the runway to the exam area, Comolli lets out a small squeal of excitement.

“They’re just the sweetest, just perfect animals. They move like little grub worms,” she said affectionately. “I call them angels.”

They do look angelic with their big, round, expressive eyes and their beautiful long whiskers.

They let Comolli examine their flippers, feeling for any abnormalities. Then they bounce right back up the runway, full of fish treats the trainer and Comolli tossed them, and off to new adventures.

Comolli is off to new adventures as well.

She has been working in a specialty referral practice in south Florida, returned as a relief veterinarian for the Georgia Aquarium, and recently accepted a relief position at a renowned zoo.

She’s also working on a project with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources that she joined in her first year during residency, performing surgery on an endangered species of fish to enable scientists to track the fishes’ movements.

She utilizes a specialized operating table that keeps a water-anesthetic solution continuously flowing over the fish’s gills so that the fish can be maintained out of the water while she performs the surgeries.

In the meantime, Comolli’s spending what little free time she has studying for what’s arguably the most difficult specialty exam in the vet world: the American College of Zoological Medicine board certification. (Divers, Mayer and Rivera are diplomates of the college.)

The two-day test covers just about everything—aquatic animals, zoo animals, exotic pets, wildlife and more. The test is considered one of the most difficult to pass, but Comolli is striving to be as prepared as possible.

“We learn a lot of advanced techniques and internal medicine during our residency here,” Comolli said. “This is probably one of the top facilities to learn exotic endoscopy, which allows us to use a tiny camera to examine the entire body cavity of an animal. Coming here allowed me to get extra experience in that technique with inarguably one of the best endoscopists for exotic animals in the world.”

Written by: Leigh Hataway

Photography and videography courtesy of Georgia Aquarium, Zoo Atlanta, Christopher B. Herron, Stephen Divers

Design by: Andrea Piazza