Catch and Release

Researchers at the Savannah River Site study wildlife ecology, disease ecology, biogeochemistry, and forestry and conservation.

Deep in a South Carolina forest, just off the edge of a murky swamp, a 190-pound wild pig has found itself in a bind.

While eyeing what seemed like easy pickings, a pile of dried corn left unattended, the lone boar had rooted himself into a sophisticated net pig trap. He’s sealed in.

Escape proves futile. Over and over, the boar charges, tusk-first, into the flexible but resilient black netting that surrounds him. Each time, he harmlessly bounces off as if it were a sideways trampoline.Eventually, the boar sees a man quietly approaching. He wears a red Georgia Bulldogs baseball cap and carries what appears to be a high-powered rifle. The man, wildlife researcher James Beasley, is followed by more than a dozen others.

In case you’re worried, the boar will be fine.

The rifle isn’t armed with live ammo. Instead, it’s loaded with a syringe-dart carrying a dose of Telazol and Xylazine, a mixture of chemicals to anesthetize the pig.

That includes investigating wild pigs’ impact, movements, and reproductive ecology. While these animals have been in the U.S. for centuries, scientists still have a lot to learn about their ecology, and Beasley’s work is helping to fill in some of the blanks.

In some ways, this is the boar’s lucky day.

Invasive wild pigs are destroying natural environments and farmland across the Southeast, tearing up landscapes with their incessant rooting and eating just about anything that can’t run away. And in recent decades, they’ve spread rapidly.

These clever feral cousins of domestic pigs can be dangerous and tricky to capture. So, typically, when swine wander into a trap like this one—for example, on a farm where they’ve been destroying crops—they are routinely exterminated.

This trapped pig, on the other hand, will only be out a few vials of blood for scientific study.

The Best Ten Days of the Year

The mix of 14 undergraduate and graduate students traveled to Aiken, South Carolina, (about half an hour east of Augusta) in mid-May for Field and Molecular Techniques in Wildlife Research and Management, a course Beasley calls his “favorite 10 days of the year.”

“This is all about getting their hands dirty,” Beasley says. “We take many of the things they learned in the classroom and apply it in a field setting.”

Every day, the students tromp into the woods at the Savannah River Site to field test the skills and lessons they’ve learned in school.

UGA’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory lies within the U.S. Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site, which is made up of a former nuclear production facility surrounded by about 310 square miles of forests, waterways, and wetlands. The place is teeming with diverse wildlife species.

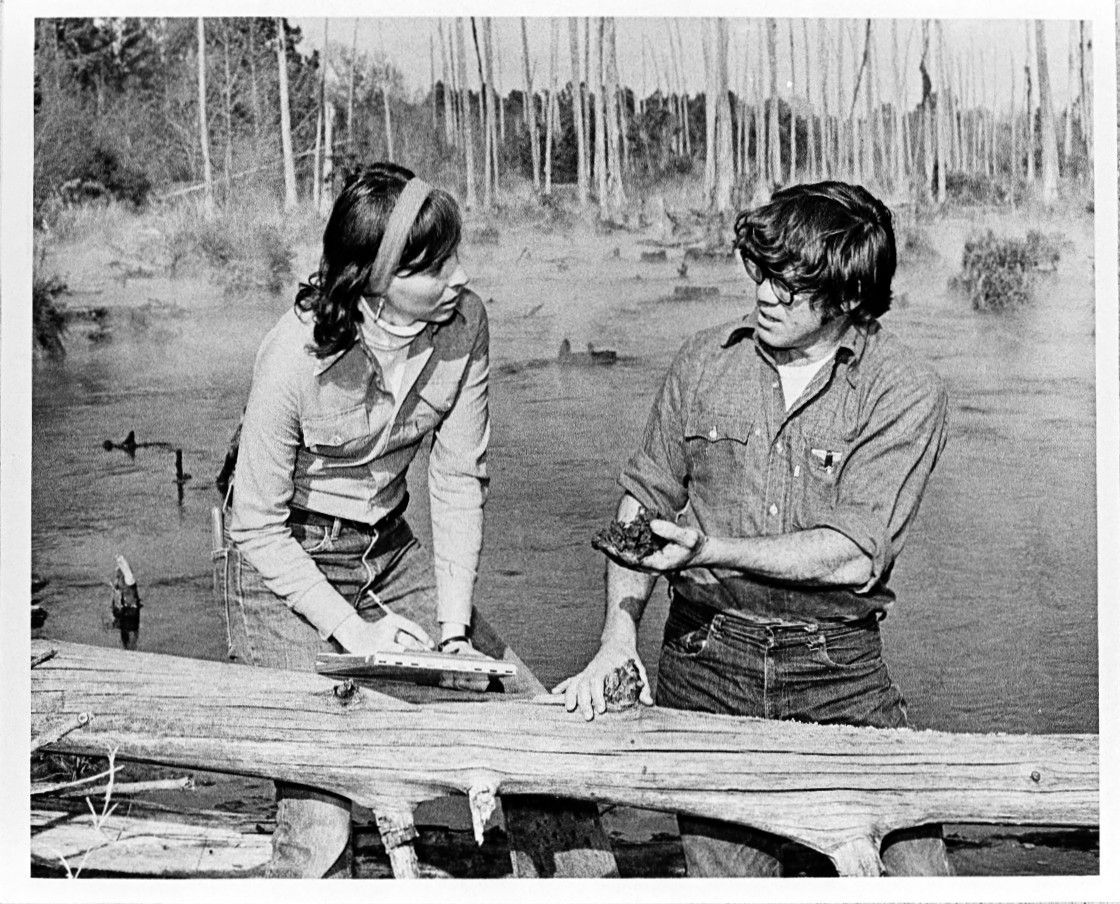

While in the wilderness, students practice baiting and placing traps to capture various critters (raccoons, opossums, mice). After they catch an animal, Beasley sedates it and then coaches the students as they collect data from the chemically immobilized animal. This is called “processing.”

Students are as gentle handling these vulnerable creatures as they would be with their own pets. Often, they even nickname the animal as they take its temperature, weigh it, draw blood, get a tissue sample, remove any ticks for analysis, check its teeth for evidence of its age, and tag it (usually with a small piece of plastic on its ear).

For Natalie Heyward, a fisheries and wildlife major from Stone Mountain, handling the animals is the best part of the course. Coming in, Heyward was planning to get a veterinary medicine degree and work in a zoo. This trip was a chance to test out that goal and get up close with the animals.

“It’s not every day you get to hold a raccoon,” says Heyward, who has already worked with cats and dogs in a vet clinic. “Every animal is different. Raccoons are just interesting to work with. They’ve got cat anatomy and dog behavior.”

They’re also adorable when sleeping.

Heyward and several other students audibly fawn when Beasley tells them that one of the raccoons they’ve trapped is an expectant mother.

They nickname her Martha.

Humans and Wildlife

As the group approaches the trapped boar, it snorts and stares down Beasley, who quietly settles just outside the trap. The pig seems to consider charging but instead attempts another escape and bounces off the netting once again. Finally, the boar turns to face Beasley, defiantly glaring at him, practically daring his tormentor to enter the trap.

Instead, Beasley slowly raises his rifle and waits for an opportunity to get a shot at the thick muscle of the pig’s hind leg. The dart hits the target, the syringe injects its anesthesia, and eventually the pig settles in for a chemically induced nap.

Since joining UGA in 2012, Beasley has caught his share of these and other creatures, ranging from scavenging beetles and rat snakes to ring-necked ducks and Eurasian gray wolves. With every wild animal Beasley studies, he’s exploring the impact of human activities on wildlife populations.

“We live on the landscape and so do wildlife, and we have a profound impact on many of these species,” Beasley says. And wildlife can affect us too. Many new infectious diseases, for example, often originate in wildlife species before jumping into humans.

As we learn more about these impacts, Beasley says, we can mitigate the worst of them with management and conservation strategies.

While most of Beasley’s work focuses on the Savannah River Site, his work takes him all over the world. He’s been to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine to explore how wolves and other carnivores appear to thrive—even in the presence of high radiation levels—now that they have no direct human interaction. In Japan, he’s helped monitor radiation near the site of the Fukushima nuclear disaster by putting GPS trackers on snakes and wild boar. And this fall, he’s headed with a multinational team to Namibia, where large predators are escaping through fences at national parks and then feasting on the local cattle.

Find the Right Path

Throughout the class, Beasley introduces the students to the work of other scientists at the Savannah River Site (a USDA Forest Service wildlife biologist who is fostering red-cockaded woodpecker nests and a UGA herpetologist surveying amphibians and reptiles in a wetland, to name a few). And he makes it a point to check in with each student one-on-one throughout the course so that he can talk with them about their individual career goals and interests.

As the students take in the 10 days of wildlife field research, they get a feel for their passion and their tolerance for a career that’s at times thrilling, uncomfortable, gross, and heartbreaking—but also deeply beautiful.

For Heyward, it was a lot to consider. Ultimately, she says, “This course kind of helped me to solidify that I am on the right path.”

Some pig!

Back at the swamp, the anesthetized boar has begun to snore.

It takes two students to drag the limp, nearly 200-pound pig out of the trap. Still, they are careful not to pull him over any of the nubby cypress knees protruding from the dark soil. As the students get to work on the boar, someone suggests the name Wilbur.

Careful to finish processing long before the boar wakes in a couple of hours, they work quickly. To keep his body temperature from rising too high, they place gallon-sized ice bags across Wilbur’s malodorous skin. And then, as if in a scene from a medical drama, the students crowd over the boar, passing out supplies and samples and announcing each data point for recording. After more than a week working on other animals, the students now seem like professionals.

When it’s time for Beasley to open Wilbur’s mouth to check his teeth, several students momentarily cringe in olfactory disgust.

“If you haven’t smelled pigs’ breath, you’ve got to try it,” quips Beasley. “It’s Yankee Candle’s next scent.”

But no one is squeamish for long. Ignoring the halitosis, the students come closer as Beasley estimates Wilbur’s age by his teeth, at least 3 years old.

After the processing is complete, Wilbur is dragged back into the trap to sleep off the anesthesia undisturbed. When he wakes up, he will be released, and he’ll venture back into the black swamp relatively unchanged except for an additional ear tag and a couple dozen fewer ticks.

The Savannah River Ecology Laboratory

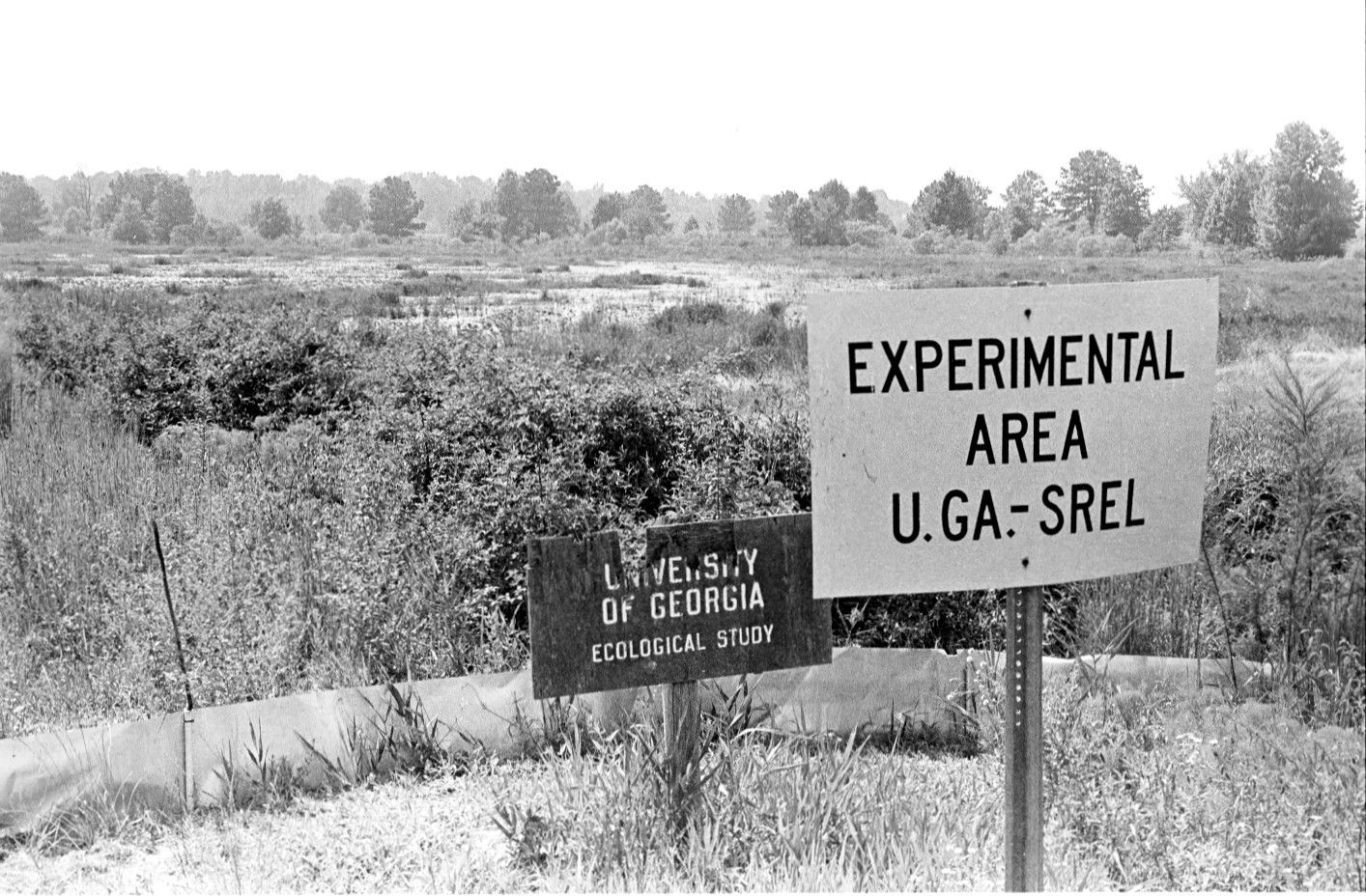

Seventy years ago, UGA zoology professor Eugene Odum stood in midst of miles and miles of farmland near Aiken, South Carolina. The U.S. government had allocated the area to build a nuclear weapons production facility.

The Atomic Energy Commission charged Odum, now known as the “father of modern ecology,” with the task of conducting ecological surveys of plants and animals before the plant’s operations began. That research served as a baseline for comparative study to assess if the operations at the plant were altering the natural environment surrounding the facility.

The project would eventually grow into the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, which continues to conduct research at the Savannah River Site. The lab’s research now includes wildlife ecology, disease ecology, biogeochemistry, and forestry and conservation.

Over generations, the lab has also informed the public through public outreach and education. Nearby students can expect visits from UGA scientists, who talk about their work and even bring a few critters along for students to see and touch.

In 2020, UGA took on an expanded role with the Savannah River Site when it joined the Battelle Savannah River Alliance, a consortium of universities and private firms selected by the Department of Energy to manage one of the country’s premier environmental, energy, and national security research facilities—the Savannah River National Laboratory (SRNL).

Written by: Aaron Hale

Photography by: Dorothy Kozlowski, UGA Special Collections

Design by: Andrea Piazza

Videography by: Corey O’Quinn, Brett Szczepanski