Where Do Broken Hearts Go?

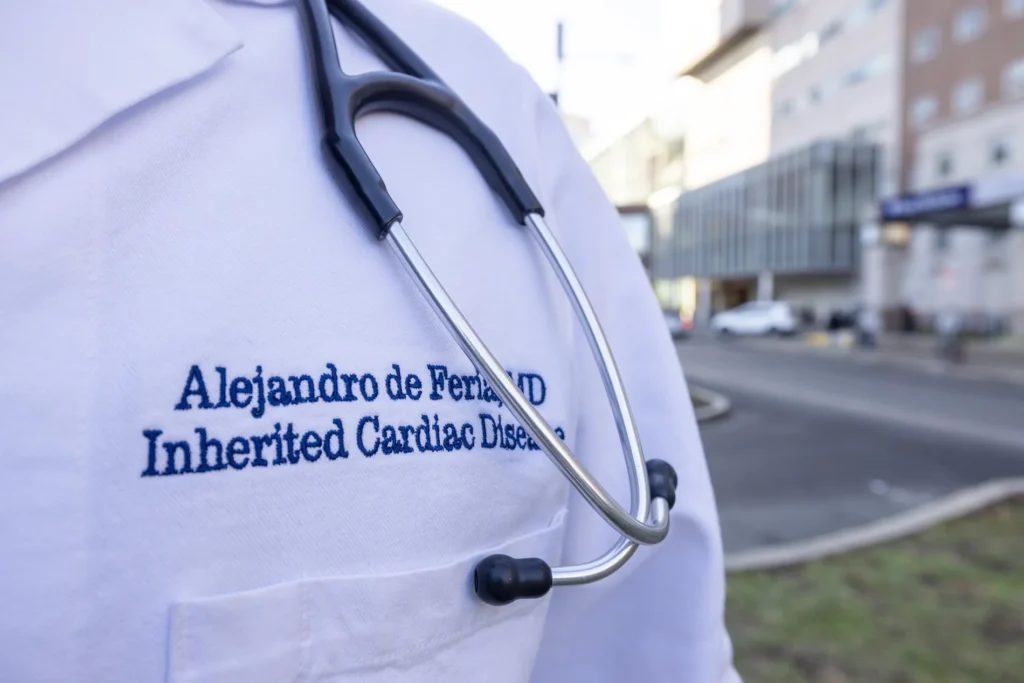

Alejandro de Feria is an expert in the human heart.

How often does someone become aware of their heartbeat? Maybe they feel it thumping in their chest during a run or listen to it stutter during a scary movie. For Dr. Alejandro “Alex” de Feria Alsina BS ’10, listening to heartbeats is the cornerstone of his profession.

De Feria is a cardiologist at the center for inherited heart disease at the University of Pennsylvania. As an assistant professor of clinical medicine, he works closely with patients and their families to navigate the complex challenges of genetic heart disorders. While the science is cutting edge, his approach is deeply human.

How do You Treat Genetic Heart Conditions?

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, almost 700,000 people die from heart disease every year. Having blood relatives with heart disease can greatly increase that risk.

De Feria studies and treats people with hereditary conditions like dilated cardiomyopathy where the heart chambers dilate and weaken, as well as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which causes the heart muscle to thicken and potentially obstruct blood flow. Both genetic conditions put patients at a higher risk of heart failure. While the genetic risk may be present at birth, symptoms can lay dormant until adolescence or adulthood.

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy affects about one in 500 people,” says de Feria. “It’s common enough that everyone knows someone who has it, whether they realize it or not.”

Until recently, many of the treatments used to treat genetic heart conditions were borrowed or adapted from other areas of cardiology and were only moderately effective. Today, de Feria’s work spans clinic visits, hospital care, and clinical trials for targeted therapies and gene-based treatments. He is involved in ongoing trials with fellow University of Pennsylvania researchers focused on targeted therapies for genetic heart disease.

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy affects about one in 500 people. It’s common enough that everyone knows someone who has it, whether they realize it or not.”

Dr. Alejandro de Feria

“I used to have to offer patients open heart surgery to fix a problem, but now we have targeted medicines and catheter-based procedures,” says de Feria. “As gene therapy becomes a reality, I am hopeful that during my career the field will shift from treating disease complications to offering cures.”

A Treatment Versus a Cure

De Feria has patients from their teens to their nineties, often in the same family.

“Many young people struggle with accepting a diagnosis, especially when it’s genetic,” says de Feria. “They’ve seen other people in their family deal with serious issues, and they think, ‘That’s not me. I’m not going to have that.’ I want people to know that even though it’s scary, plenty of people live with these conditions and can have good lives.”

For those with genetic risk who do go on to develop disease, de Feria does his best to treat the symptoms and reduce the chance of heart failure. He encourages all his patients to focus on quality of life.

De Feria vividly remembers the limitations put on patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, but a lot has changed since he started studying medicine.

“In the early 2000s, exercise for kids with HCM was restricted to bowling or golfing with a cart, and that was about it. Now there are professional athletes who have these conditions and continue to play,” he says. “My hope is that we’ll continue to improve disease detection and treatment to help families change the trajectory of their health outcomes across generations.”